NEW YORK, NY | Monday Sep 25, 2017 | Anita Ravi, M.D., M.P.H., M.S.H.P.

Original article can be found at: http://www.aafp.org/

_____

Graham-Cassidy is not a health care bill.

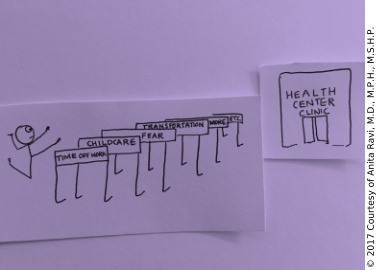

It’s a health care wall, and it’s a new wall in a system that already has too many barriers between doctors and patients.

The condition of our health care system has been improving. We have been breaking down walls across medicine, seeking remedies through investments that address social determinants of health, adverse childhood events, implicit bias and health equity. But these advances would become relics with the implementation of the so-called Graham-Cassidy bill that’s being considered in the Senate.

Although many of us in medicine routinely provide care for vulnerable populations, Graham-Cassidy — so named for two of its sponsors: Sens. Lindsey Graham, R-S.C., and Bill Cassidy, R-La. — threatens a precipitous increase in the number of people who will be uninsured. Such an increase would shape what “routine health care” means.

As a physician in a federally qualified health center (FQHC) safety-net clinic in New York where the majority of my patients are uninsured or underinsured, delivering care with limited resources is a normal part of my work. And it remains the most challenging. Unfortunately, a health care bill sprinkled with placebo promises of “affordable” and “adequate” health insurance coverage provides no relief — for me or my patients. Clinical experience has taught me that such language rarely anticipates the needs of those most vulnerable patients, and it does not deliver the resources needed for quality patient care.

Based on my experience with patients in these circumstances, here are a few issues that risk normalization if this bill passes.

Board exams do not prepare us to work with underinsured patients. There are no exam questions asking what we should choose if a patient has asthma, diabetes and high blood pressure but can only afford one lab test. But this is the type of question I frequently face, and these scenarios threaten to become the norm during our clinic visits should the Graham-Cassidy bill be implemented.

In medical school, we are trained how to deliver bad news. Discussing life-changing diagnoses such as cancer, HIV and miscarriages requires sensitivity and practice. But training I sorely lacked was delivering bad news to my patients regarding the cost of their care. It was an issue I thought I was immune to. I thought that as long as I followed the correct algorithms and ordered the correct tests and imaging, that I was always doing right by the patient. But medical standards of care do not account for patients’ socioeconomic circumstances, and overlooking this jeopardizes physician-patient relationships.

In a Graham-Cassidy era, these challenging conversations will grow to become instinctive as the rate of uninsured and underinsured people in this country increases. But beware: Standard-of-care medical guidelines abandon patients who cannot afford them, and the conversations never become easier.

Creative problem-solving when a patient cannot afford care is a skill I’ve reluctantly admitted to needing, and it will undoubtedly become a new standard of care — with caps on costs, particularly for pre-existing conditions, if Graham-Cassidy becomes law. Begging specialists to consult on a patient who cannot afford their expertise, strategizing with pharmacists to connect a patient with an affordable medication and brainstorming fundraising efforts for the patient whose case you can’t stop thinking about are just some examples of alternative infrastructure and algorithms of care that must be created to fill in the gaps of patient care.

In a Graham-Cassidy era, such exercises of forced creativity will not be rarities, but commonplace necessities, as gaps in affordable care grow into chasms. These will be cases that keep you up at night.

Women, particularly those with low incomes(www.kff.org), will be greatly affected by the Graham-Cassidy bill. These are the women I see at the PurpLE Clinic(www.facebook.com), a program in our FQHC for survivors of sexual violence and human rights abuses. Many of them have largely benefited from the Medicaid expansion in New York. Sometimes they share their experiences about how they accessed care before insurance, when the ER was their primary medical home.

A Graham-Cassidy world of slashed funding for women and vulnerable populations will make this past a regressive new reality. And these stories will become a routine part of our medical notes.

Our current system is by no means perfect, and I hope that it can be transformed through an effective and sustainable solution. But I know that the path to its improvement would be blocked by the Graham-Cassidy wall.

As family physicians, the trauma of repeated threats of uninformed health care bills wears on us. We do our best to speak up and Speak Out. We recognize health as a human right. And yet, whenever we’re pacified by progress in health care delivery, we’re dealt news that we may be at risk for recurrence of cancerous policies that impair our ability to do our job.

Graham-Cassidy is not a health care bill. It’s a wall. Another wall that we certainly cannot afford to build.

Anita Ravi, M.D., M.P.H., M.S.H.P., is the founder and clinical director of the PurpLE Clinic at the Institute for Family Health in New York City. She is not an artist, but enjoys using stick figures to promote health and gender equity. You can follow her on Twitter @anitafamilydoc(twitter.com).

Share this Post